|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

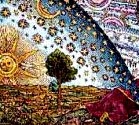

The very first word of the Torah indicates the awareness of the significance of time - בראשית -"in the beginning..." (Genesis 1:1), and according to Rabbinic tradition, the very first commandment given to the children of Israel after being delivered from Egypt was to sanctify the "New Moon" (Exodus 12:1-2), thereby causing the fledgling nation to depart from the solar tradition of the Egyptians (Ra worship) and to look to the moon for a new means of reckoning time and seasons.

The Hebrew lunar calendar (i.e., luach ha'yare'ach ha'ivri: לוח הירח העברי) is "set" differently than the solar calendar. The day begins at sundown; the climactic day of the week is Shabbat - the seventh day of the week; the moon and its phases in the night sky are the timepiece for the months, and the seasons of the year are marked with special festivals or mo'edim (appointed times). Even the years are numbered: every seventh year was sh'mitah - a Sabbatical year (Lev. 25:2-5), and after seven cycles of sh'mitah the Yovel, or Jubilee Year was to be observed (Lev. 25:8-17). Indeed, according to the Jewish sages, the history of the world may be understood as seven 1,000 year "days," corresponding to the seven days of creation. In fact, the Talmud (Avodah Zarah, 9A) states that the olam hazeh (this world) will only exist for six thousand years, while the seventh millennium will be an era of worldwide shalom called the olam haba (world to come).

|

|

|

|

|

|

A Luni-Solar Seasonal Calendar

Actually, the Jewish calendar might best be described as "luni-solar." Since every lunar cycle runs roughly 29.5 days, the Jewish year has 354 days compared to 365 days of the solar calendar. To ensure that the festivals would occur in their proper seasons (e.g. Passover in springtime, Sukkot in the fall, etc.), an extra month (Adar II) is added every two or three years to offset the 11 day lag per solar year. In this way the lunar calendar is synchronized with the solar cycle of the agricultural seasons.

|

|

|

|

|

The western sense of time is basically the measurement of linear, progressive motion, but in Hebrew thinking, time is seen as an ascending helix, with recurring patterns or cycles that present a thematic message or revelation of sacred history. Indeed, part of being a Jew today is to be mindful of this divinely ordered spiral of time and to order our affairs accordingly.

|

|

|

|

|

The Jewish Day

|

|

|

|

The Hebrew day (yom) begins at sundown, when three stars become visible in the sky (the rabbis reasoned that the day begins at sunset based on the description of God's activity in creation, "and the evening and the morning were the first day," Genesis 1:5). Evening is sometimes defined as the late afternoon, that is, between 3:00 pm to sundown.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Since the Jewish day (yom) begins at sundown, you must remember that a Jewish holiday actually begins on the night before the day listed in a Jewish calendar. For example, Yom HaShoah (Holocaust Memorial Day) occurs on Nisan 27, which actually begins after sundown on the previous day:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thus a given Jewish holiday spans two days on our Gregorian calendar. Most Jewish calendars do not indicate the previous night as part of the holiday. Observance of a holiday begins at sundown on the day before it is listed in the calendar!

|

|

|

|

|

In the example above, Yom HaShoah is observed both on Thursday the 5th (after sundown) and Friday the 6th (during daylight hours).

Note that if a Jewish holiday were to occur on a Sabbath, it would be moved to the previous Thursday on the calendar. For example, if Nisan 27 happened to begin on Friday at sundown, it would be moved to Nisan 26. Accessing a current Jewish calendar is essential to observing the mo'edim!

|

|

|

|

A Note about the Jewish Hour (sha'ah)

|

|

|

|

In rabbinical thinking, the hour (שָׁעָה) is calculated by taking the total time of daylight (from sunrise until sunset) of a particular day and dividing it into 12 equal parts. This is called sha'ah zemanit, or a "proportional hour."

Since the duration of daylight varies according to seasons of the year, a proportionate hour will therefore vary by season. The "sixth hour of the day" does not mean 6:00 a.m. or even six 60 minute hours after sunrise, but is the 6th proportionate hour of the 12 that are counted for the day in question.

For example, if the sun rises at 4:30 a.m. and sets at 7:30 p.m., the total time of daylight is 15 hours. 15 hours * 60 minutes is 900, which divided by 12 yields a proportional hour of 75 minutes. The "sixth hour of the day" therefore begins 450 minutes after sunrise, or about 11:30 in the morning.

The calculation of these zemanim ("times") are important for the observance of Jewish holidays and Sabbath candle lighting hours. The results will vary depending on the length of the daylight hours in the particular location.

|

|

|

|

|

The Jewish Week

|

|

|

|

The Jewish week (shavu'a) begins on Sunday and ends on Shabbat:

|

|

|

|

|

|

days of the week

|

|

|

|

|

- The Importance of Shabbat

The fourth of the ten mitzvot (commandments) is, "Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy" (Ex. 20:8, KJV). Shabbat is therefore considered to be the most important day of the week, since the observance of Shabbat is explicitly set forth as one of the Ten Commandments. In fact, Shabbat is considered the most important of the Jewish Holidays, even more important than Rosh HaShanah and Yom Kippur!

During Shabbat, no "work" (defined under 39 main categories associated with the building of the Tabernacle in the desert) is to be performed, since this would violate the idea of "rest" (shabbaton) that is to mark the day.

- Weekly Torah Readings

Weekly Torah readings are divided into 54 sections. A given weekly section is called a parashah (pl. parashiyot) and is read during a synagogue service. Each portion has a Hebrew name (usually the first word of the section). A haftarah is a reading from the Nevi'im (prophets) that is recited directly following the Torah reading. For a table of the weekly readings, click here.

|

|

|

|

Jewish Months

|

|

|

|

The duration of a Hebrew month (chodesh) is measured by the amount of time it takes for the moon to go through a lunar cycle, about 29.5 days:

|

|

|

|

- Rosh Chodesh

The appearance of the new moon is called Rosh Chodesh ("head of the month"). Twelve chodeshim make a Shanah, or year. The new moon is observed in synagogues with additional prayers.

- Lunar Leap Years

Since the solar year is 365 days long but a moon year is only 354 days (29.5 x 12), an extra month is added to the Hebrew calendar every two or three years. The formula is a bit esoteric, but every 19 years there are seven leap years (the third, sixth, eighth, eleventh, fourteenth, seventeenth and nineteenth years). In a leap year a 13th month is added called Adar Sheni (Adar II).

In the Tanakh, the first month of the calendar is Nisan (when Passover occurs - see Exod. 12:12); however, Rosh Hashanah ("head of the year") is in Tishri, the seventh month, and that is when the year number is increased.

|

|

|

|

|

The Jewish Year (שָׁנָה שֶׁל עִבְרִית)

|

|

|

|

The Jewish year is cyclical, with seasonal holidays and festivals. The names of the months of the Jewish calendar year were adopted during the time of Ezra the Scribe, after the return from the Babylonian exile.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

months of the year

|

|

|

|

|

The three bold-faced festival names are known as Shalosh Regalim, the three "Pilgrim Festivals" (Exod. 23:14), that focus on key national events in Israel's history (i.e., the Exodus). These festivals mark the three times in the yearly liturgical cycle when all Jews are required to go up to Jerusalem to pray and sacrifice. Today, Jews mark these times with extended worship and prayer, study, distinctive prayer melodies, and festive meals.

The Jewish High Holidays run from the ten days from Rosh HaShanah to Yom Kippur and focus on individual repentance (teshuvah).

The date of Jewish holidays does not change from year to year. However, since the Jewish year is not the same length as the solar year on the Gregorian calendar, the date will appear to "shift" when viewed from the perspective of the Gregorian calendar.

|

Four Jewish New Years

You might be surprised to discover that by the time the Mishnah was compiled (200 AD), the Jewish sages had identified four separate new-year dates for every lunar-solar year (the modern Jewish calendar was ratified by Hillel the Elder in the 3rd century AD):

- Nisan 1 (i.e., Rosh Chodashim) marks the start of the month of the Exodus from Egypt and the beginning of Jewish national history. As such, it represents the start of the Biblical year for counting the festivals (Exod. 12:2). Note that the month of Nisan is also called Aviv since it marks the official start of spring.

- Elul 1 marks the start of the year from the point of view of tithing cattle for Temple sacrifices. Since the Second Temple was destroyed in 70 AD, the rabbis decreed that this date should mark the time of Selichot, or preparation for repentance before Rosh Hashanah. Elul 1 marks the start of the last month of summer.

- Tishri 1 was originally associated with the agricultural "Feast of Ingathering" at the "end of the year" (Exod. 23:16, 34:22), though after the destruction of the Second Temple, the sages decided it would mark the start of the civil year in the fall. Tishri 1 was therefore called Rosh Hashanah ("the head of the year") which begins a ten-day "trial" of humanity climaxing on the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur).

- Shevat 15 (i.e., Tu B'Shevat) originally marked the date for calculating the tithes of the harvest (ma'aserot) that farmers would pledge to the priests of Israel. This was the start of the year from the point of view of tithing of fruit trees. Today Tu B'Shevat represents a national Arbor Day in Israel, with tree planting ceremonies in Israel. Unlike the other three "new years," Tu B'Shevat begins in the middle of the month, during a full moon in winter.

In practical terms, however, there are two "New Years" in Jewish tradition. The first occurs two weeks before Passover (Nisan 1) and the second occurs ten days before Yom Kippur (the other two "new years" are not regularly observed, except by the Ultra Orthodox). The first New Year is Biblical and is called Rosh Chodashim (see Exod. 12:2). This is the month of the redemption of the Jewish people -- and it is also the month in which Yeshua was sacrificed upon the cross at Moriah for our sins. Oddly enough for most Christians, "New Years Day" should be really celebrated in the Spring....

The "Dual Aspect" Calendar

In this connection, notice that the calendar is divided into two equal parts of exactly six lunar months each, both of which center on redemptive rituals and end with harvests. The first half of the divine calendar begins on Rosh Chodashim (i.e., Nisan 1; Exod. 12:2), which is followed by the instruction to select the Passover lamb on Nisan 10 (Exod. 12:3), slaughter it in the late afternoon of 14th (Exod. 12:6-7) and eat it on the 15th (Exod. 12:8). The Passover itself initiated the seven day period of unleavened bread (from Nisan 15-22), wherein no leaven was to be consumed (Exod. 12:15-20). On an agricultural level, Passover represents spring, the season of the firstfruit harvests (i.e., chag ha-katzir: חַג הַקָּצִיר), and so on. On the "other side of the calendar," Yom Teruah (or Rosh Hashanah) marks the start of the second half of the year (Exod. 23:16, Lev. 23:24), which is followed by the Yom Kippur sacrifice ten days later, on Tishri 10 (Lev. 23:27), followed by the weeklong festival of Sukkot ("Tabernacles") that occurs from Tishri 15-22 (Lev. 23:34-36). On an agricultural level, Sukkot represents the reaping of the the fall harvest (i.e., chag ha'asif: חַג הָאָסִף) at the "end of the year" (Exod. 23:16). In other words, in some respects the fall holidays "mirror" the spring holidays on the divine calendar, and indeed, both sides of the calendar represent different aspects of God's redemptive plan for the world. As I've written about elsewhere, the spring holidays represent the first advent of Yeshua (i.e., Yeshua as Suffering Servant, Lamb of God, Messiah ben Yosef), whereas the fall holidays represent His second advent (Yeshua as Conquering Lord, Lion of the Tribe of Judah, Messiah ben David).

Cycles of Time...

As mentioned above, instead of thinking of time as a linear sequence of events (i.e., the measurement of motion), Jewish thinking tends to regard it in terms of a spiral or "helix," with a forward progression delimited by an overarching (and divine) pattern that recurs cyclically throughout the weeks, months, and years of life. This can be seen in the Hebrew language itself. Some of the sages note that the Hebrew word for "year" - shanah (שָׁנָה) - shares the same root as both the word "repeat" (שָׁנָה) and the word "change" (שִׁנָּה). In other words, the idea of the "Jewish year" implies ongoing "repetition" - mishnah (מִשְׁנָה) - or an enduring "review" of the key prophetic events of redemptive history as they relived in our present experiences... (The idea that the events of the fathers were "parables" for us is expressed in the maxim: מַעֲשֵׂה אֲבוֹת סִימָן לַבָּנִים / ma'aseh avot siman labanim: "The deeds of the fathers are signs for the children.") The Jewish year then repeats itself thematically, but it also changes from year to year as we progress closer to the coming Day of Redemption... We see this very tension (i.e., constancy-change), for example, in the "dual aspect" of the ministry of Yeshua our Messiah. In His first advent Yeshua came as our Suffering Servant and thereby fulfilled the latent meaning of the spring holidays, and in His second advent He will fulfill the latent meaning of the fall holidays. Nonetheless, we still commemorate both the "type and its fulfillment" every year during Passover by extending the ritual of the Seder to express the reality of Yeshua as the world's "Lamb of God," just as we commemorate the fall holidays in expectation of His rule and reign as our King....

None of this is meant to suggest, by the way, that there isn't an "end point" in the process - a Day in which we will be with God and enjoy His Presence forever... The idea of the "cycles" of time, or "timeless patterns within time," suggests, however, that the "seed" for our eternal life with God has already been sown - and was indeed foreknown even from the Garden of Eden - despite the fact that we presently groan while awaiting the glory of heaven...

How to calculate the Jewish Year

The year number on the Jewish calendar represents the number of years since creation, calculated by adding up the ages of people in the Tanakh back to the time of creation. To calculate the Jewish Year from our Gregorian calendar, you subtract 1,240 and then add 5,000. For example, if the year is 2005, subtract 1,240 to get 765. Then add 5,000 to obtain the Jewish year of 5765. Note that this works only up to Rosh Hashanah of the current Gregoraian calendar: after Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year) add one more year (e.g., 5766). For information about how to write the Hebrew year, click here.

How to determine Jewish Leap Years

A year is a Jewish "leap year" if the number year mod 19 is one of the following: 0, 3, 6, 8, 11, 14, or 17. Use a scientific calculator with the mod function to determine the result. For example, 5771(mod)19 = 14, indicating that it is a leap year.

What is the true Jewish Year?

Some have said that the Jewish Year counts from creation but excludes the various years of the captivities, while Rabbinical tradition states there are about 165 "missing years" from the date of the destruction of the First Temple to the date of the destruction of the Second Temple. Others suggest that there are some missing years in the Hebrew calendar due to a corruption in the accounting of the years of the Persian monarchies, and that these years were consciously suppressed in order to disguise the fact that Daniel's prophecy of the 70 weeks pointed to Yeshua as the true Mashiach of Israel. In short, educated uncertainty exists regarding the exact year we are living in since the Creation of the Universe by God...

|

|

|

|

The Jewish Festival Seasons - Mo'edim

|

|

|

|

Jewish time is cyclical and prophetic, a sort of a ascending spiral to God. The observant Jew will pray three times every day. On the seventh day of the week, Shabbat is celebrated, as is Rosh Chodesh at the start of the new month. In addition, the various larger periods of time, seasons, have their own prophetic role and function in the overall rhythm of Jewish life.

Note: The Jewish calendar can be a bit tricky to understand, especially if you are new to the study of the Jewish way of thinking about time!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In particular, you must remember that a Jewish holiday begins on the evening previous to the day indicated on a Jewish calendar (unless that happens to be a Sabbath, in which case the date is moved earlier). For example, Yom HaShoah (Holocaust Memorial Day) occurs on Nisan 27 - unless that day is a Sabbath - in which case it is moved earlier to Nisan 26 (whenever in doubt, consult an authoritative Jewish calendar).

|

|

|

|

|

Spring - Deliverance

|

|

|

|

- Passover (Pesach) - Celebration of freedom (Major Holiday)

- Pentecost (Shavu'ot) - The giving of the Torah at Sinai and the giving of the Ruach HaKodesh to the Church [Sivan 6-7] (Major Holiday)

|

|

|

|

The Gregorian Calendar, considered to be a revision to the Julian Calendar (which was itself a revision of the pagan Roman/Greek calendars) retains most of the names of the days of the week and months of the year from pagan Rome (and therefore, ancient Greece). The ancient Greeks named the days of the week after the sun, the moon and the five known planets (Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn) which themselves were associated with the gods Ares, Hermes, Zeus, Aphrodite, and Cronus, respectively.

For more information, click here.

|

|